A more representative solution for calculating academic citations

Millions of scientific articles are published every year and released to the scientific communities using various bibliographic databases such as Google Scholar, CiteSeerX or Scopus. In order to understand the impact of a publication and how it shapes the future of the research field, citation index and citation impact measures are used. Such measures enable researchers to trace the succeeding papers that rely on their publications.

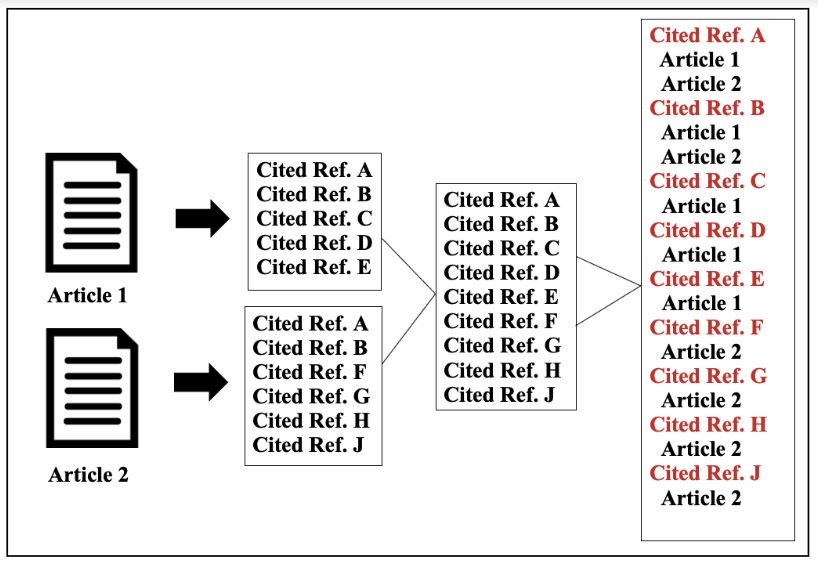

Although there are many ways to calculate citation index and impact at article-level, such as the famous h-index and many more author-level metrics, all of them seem to be sharing one strong assumption and that is, a citation is counted only when a paper directly cites another paper. The following figure illustrates how citations are calculated in Article 1 and Article 2 according to their bibliographies.

What is wrong?

Imagine, after years of study and research, you publish a seminal work in your field in a journal. Your paper is very theoretical and sheds light on a complex and unsolved problem. After a while, a few other researchers get another idea from various sources including yours, and publish another paper where your paper is also cited. In such a scenario and given the current citation calculation method, your paper would get a citation of 1. However, after a few months, it turns out that the other paper has paved the way for a new branch in your field and therefore, is being cited thousands of times in a year. Now, the question is: how your contribution and your idea that helped to untie the Gordian knot can be acknowledged properly?

Let’s take a look at an example. Paper A and C which are respectively published in 2013 and 2014, are cited 1 time. The papers that cited those given papers are themselves being cited by succeeding papers. Let’s focus on Paper B, published in 2015, which is cited 8 times. Even if Paper A provided the theoretical base that led to the authors of the Paper B to conclude with a new theorem, Paper A still has 1 citation and this may probably stay so, as the scientific community will be built upon Paper B, rather than Paper A due to the lack of direct citation of the latter. Recently, Bollmann and Elliott has addressed the same issue with a focus on the older papers in the field of natural language processing (NLP) and states that:

... recently published papers (0–3 years old) are cited significantly more often in publications from recent years (ca. 2015–2019), while papers published 15 or more years ago are being cited at a stable rate.

A solution

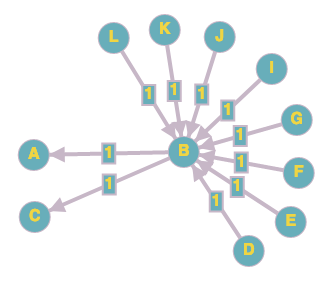

We can model the citation problem as a weighted directed graph (or also tree), where nodes represent papers and edges represent citations. The following illustrates Papers A, B and C, as mentioned earlier:

Here is a simple solution. When a paper is cited, instead of considering direct citations, all future papers that cite succeeding papers will have an impact on the current one based on their citation counts and number of papers that they cite. To further clarify, let’s get back to our graph above. Paper B cites Paper A and Paper C. The two latter papers are cited once each one. If we divide the whole number of citations of Paper B, i.e. 8, to the number of papers that it cites, i.e. 2, Paper A and Paper C each one will have 4 citation impacts. Citation impact of a paper cited by a paper that has not been cited is 0.

Therefore, we can define citation impact of paper \(i\), \(CI_i\), as follows:

\[CI_i = \sum_{j \in J}^{} \frac{CI_j}{|cite(i)|}\]where \(i\) is a given paper, \(J\) is the set of papers that directly cite \(i\), \(CI_j\) is the citation impact of the papers that cite paper \(i\) and |\(cite(i)\)| is the number of papers that paper \(i\) cites. We set the citation impact of parents of children nodes, i.e. papers which are not cited at all, as the whole number of citations.

The following shows a more detailed scenario where the impact of papers that cite B is propagated to the older citations in such a way that papers A and C have a citation impact of 5 while their direct citation remains 1.

A better weighting policy?

In the current approach, all cited papers have the same weight in calculating the citation impact. In other words, whether a paper is cited in the related work or in the methodology, it is acknowledged in the same way in terms of the citation impact. To solve this, a mechanism may be required to distinguish the importance of the cited articles from the authors’ point of view.

I think there are many ways to improve our current citation calculation systems and also the way that we write manuscripts. This simple method, despite its simplicity, provides a more comprehensive way to reflect the importance of a paper in shaping the future of a scientific field.

References

- Bollmann M, Elliott D. On Forgetting to Cite Older Papers: An Analysis of the ACL Anthology. InProceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2020 July (pp. 7819-7827) [Link].

Last updated on 18 September 2020.