"[v], idiot, [v], not [w]!"

"If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart."

I still remember that scene in front of my eyes, just like it is happening now. This is what Dyako was told, a classmate who used to sit next to me in our classroom when I was 9 and he was repeatedly beaten by the teacher. Why? He could not pronounce a phoneme correctly, because he was forced to speak in a language which was not his. And, sadly, this is still the case of millions of people around our world of the 21st century, particularly the Kurds who are forced to replace their mother tongue, Kurdish, by other languages from the very early stages of formal education.

In this post, I am going to briefly describe how being deprived of having a formal education in mother tongue influences a child’s life. Being a polyglot, I have been always wondering how education in my mother tongue might have changed the way I see the world around me.

You don’t choose it. You’re born with.

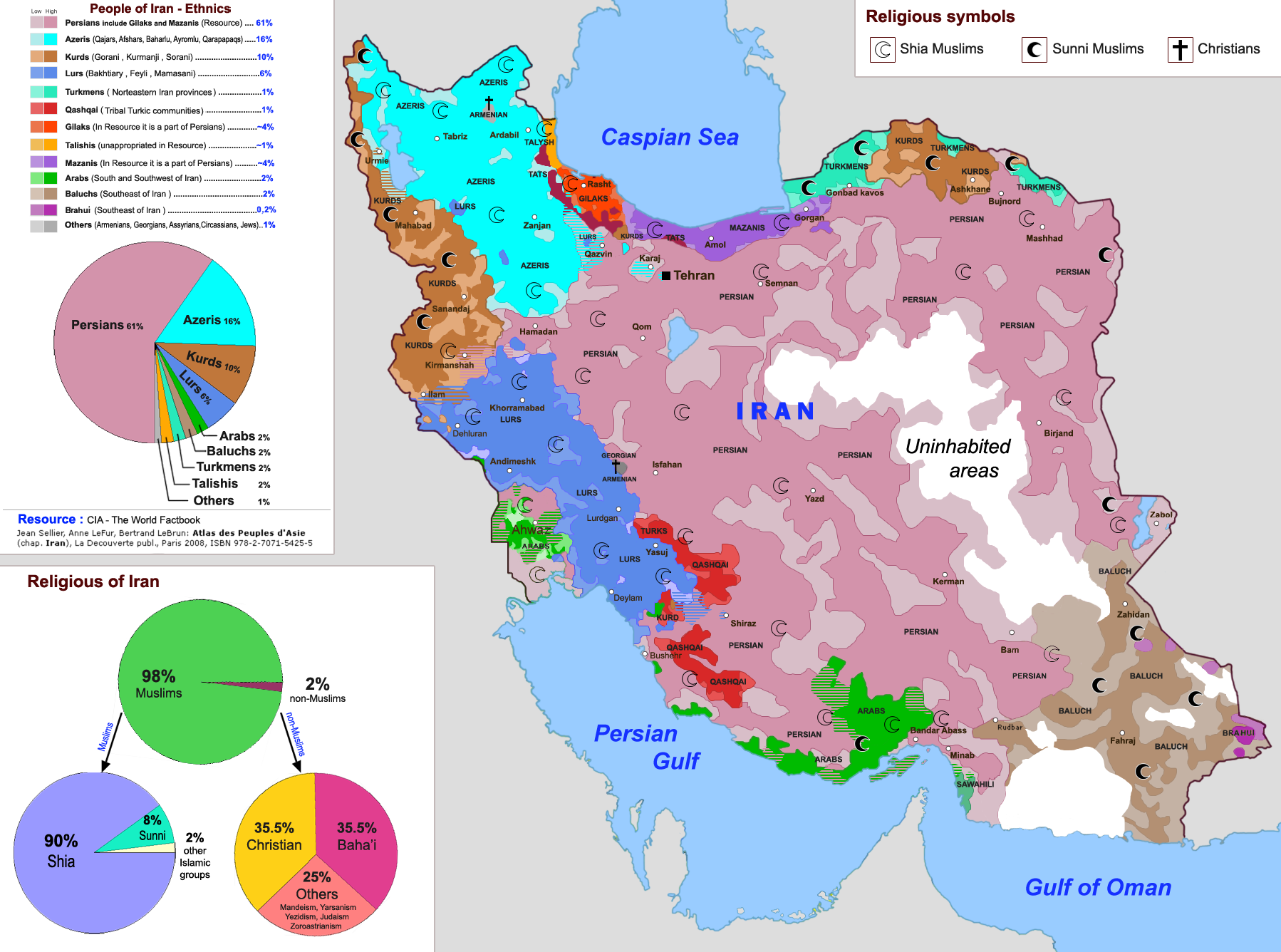

Kurds are an ethnicity of 20-30 million of population who are native to Kurdistan, a region which is geographically located in the Middle East and Caucasus, and politically, divided between four countries: Iraq, Turkey, Iran and Syria. Except the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Kurdish is recognized as the formal language of none of the three latter countries. Kurdish people, are not only culturally close to their neighbouring ethnicities, namely Turks, Persians, Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians and etc., they also speak a language which has been historically influenced by them. Kurdish, as an Indo-European language, also shares a lot of linguistic features with its neighbouring languages.

I was born and raised in the Kurdistan of Iran where the Kurdish language, in a variety of dialects, is spoken by the Kurdish inhabitants. Despite the ethnic and linguistic richness of Iran, none of them is recognized and none of their languages is supported as a formal language, even locally. Persian, also known by its endonym Farsi, is the only predominant and official language in Iran. In other words, the educational and administrative systems are only available in one single language, while almost half of the Iranian population are born with a language other than Persian. Even the name of the places, villages, cities and local traditions and products are translated into the official language and any other language is systematically disregarded.

There is a saying in Persian that “Persian is sugar”. I am sure for Dyako and all those who were and still are forced to learn it, it’s as bitter as gall!

A personality crisis

A language is a living organism which is being constantly developed. Therefore, the process of learning mother language is not limited to cognitive development in the first years of life, but a considerable amount of knowledge is obtained through intellectual development. Our lexical knowledge gets progressively enriched to describe sophisticated and abstract concepts. Independent Education Today and this article summarize the research findings about what we know about mother tongue development as follows:

- Mother tongue develops a child’s personal, social and cultural identity

- Using mother tongue helps a child develop their critical thinking and literacy skills

- Skills learnt in mother tongue do not have to be re-taught when the child transfers to a second language

- Children learning in mother tongue enjoy school more and learn faster due to feeling comfortable in their environment

- Self-esteem is higher for children learning in mother tongue

- Parent-child interaction increases as the parent can assist with homework

- Studies show that children that capitalise on learning through multilingualism enjoy a higher socio-economic status and earn higher earnings

- The level of development of children’s mother tongue is a strong predictor of their second language development.

- Mother tongue promotion in the school helps develop not only the mother tongue but also children’s abilities in the majority of school language.

- Children’s mother tongues are fragile and easily lost in the early years of school.

- To reject a child’s language in the school is to reject the child

In a situation where the usage of mother tongue is limited to inter-personal communication within the family circle, students are obliged to renounce allegiance to their mother tongue to be accepted in the dictated discourse and society. And, the distressing scenario is that the assimilation policy may ultimately make the future generations have the conviction that “my mother tongue is not good enough and just let it go”, and that’s probably the end of a language…

A linguistic crisis

There has been so much effort in protecting endangered languages and even revitalize a language. The whole point of language is to communicate. But what if a language is gradually being used less and less? How a language can remain productive with respect to the new concepts for which a word is needed?

With respect to the Kurdish language, there is a crisis not only for the speakers, but also for the language itself. I can mention two consequences as follows:

Lack of terminology

Coining words and neologisms requires a thorough knowledge about a language, but making those words live and used requires social and political support. This is simply not possible for Kurdish. Therefore, scholars struggle to speak in a “clean” Kurdish, a Kurdish without much foreign terms. Having said that, the vocabulary of the mother tongue when is not taught, undergoes unpleasant changes, particularly through word borrowing and phonology.

The state of being less-resourced

I strongly believe that one of the main reasons that Kurdish is still less-resourced, as I have already discussed, is due to lack of contribution of the speakers to create new resources and tools for the language. This is due to the usage of second languages for formal communications.

Multilingualism is an opportunity not a threat

Unluckily, the benefits of mother tongue education and multilingualism is not evident to everyone. In a country with such ethnic diversities, like Iran and Turkey, multilingualism should not be considered as a threat but as an opportunity. Learning new languages is joyful, but it should not be forced. No language is better than the others and no language deserves to be disregarded. And this is not that clear for many yet!

Last updated on 21 February 2020.