Ph.D. in Ireland vs. Europe: a comparative overview

Updates (May 5th, 2022)

Even though this blog post has remained much relevant even after two years, I don’t think I will update the collected data. However, I’ll provide a few links here for future readers as follows:

Many postgraduate students, including myself, have been recently feeling more than before ignored and exploited in Ireland, due to the lack of regulations and fair remuneration within universities. In the past few years, many student organizations have talked about our issues and tried to raise awareness among both students and university administrations about the current challenges that we are going through. A few particular examples are the unpaid teaching hours at the National University of Ireland Galway, demands for a fair working environment at NUI Galway and Trinity PhD student writes to minister demanding rent subsidy.

With the restrictions that COVID-19 imposed on our world, including Ireland, a few aspects of our lives as PhD students became more salient. If we could previously forget some of our difficulties temporarily by going out with friends and have a pint or two in the pubs, now, those are gone and the majority of us are left with a computer and a desk in, most probably, a room within a shared space. Yet this year, the icing on the cake was when we were notified that teaching hours will remain unpaid just like before despite all the current difficulties.

On a personal side, I went through a period of turmoil when I was looking for a new place to move in and was reminded every day how miserably one should adapt oneself to the mediocre accommodation situation of Ireland, having a highly infectious disease spreading around as well. What if every one of us could live in more decent conditions and could actually spend the lockdowns more peacefully by focusing on our research, obtaining new skills or spending more time with friends and family virtually?! Wouldn’t that happen by first having a private place to live in?

During many discussions with fellow students and researchers, it turned out that our rights as students are not equally understood. Although comparisons are good ways to highlight the differences between two countries, oftentimes many factors should be taken into account to have a fair comparison. Therefore, in order to have a better understanding of the current situation in comparison to other European countries, particularly Nordic countries and those in Western Europe, I collected data from various sources to answer the following questions:

- Q1: How much a PhD student is paid?

- Q2: Which countries consider a PhD student stipendiary/civil servant?

- Q3: How much does a PhD student pay to enrol for a program?

- Q4: What is the minimum wage of each country?

- Q5: How much is the average rent for a 1-bedroom flat?

I believe, to have a fair image on how PhD life looks like in a country, we should include many factors, particularly these ones. In addition, these questions may help future students, who want to pursue their PhD studies in one of the European countries, have a more comprehensive image of how their 3-4 years of PhD life would look like.

Data collection

In order to collect the data, I consulted the legitimate sources of information, such as Légifrance for France, that provide the latest rules and regulations. It is worth mentioning that finding out how PhD students are paid in different countries is not as straightforward as it may look. The European Union used to publish annual reports in their policy library, but this does not seem to be the case since 2014 (see Researcher Reports 2014, for example). As an alternative source of information, I relied on the data provided by Fastepo and, in a couple of cases glassdoor. Moreover, in countries where PhD students are paid a salary and not a stipend, there are many issues with respect to how the net salary should be calculated. Given the complexity, I only included the minimum possible salary reported in my sources for the most basic conditions, i.e. 0 year experience, 1st year of PhD, 0 year seniority. Therefore, the numbers provided here are for the most basic conditions for a PhD student.

Please note that:

- There is possibly a margin of error in the collected data.

- All values are dependent on many other factors such as student’s nationality, seniority, taxation, etc. The most frequent case is considered.

- The data are collected on September 2020.

- All the values are in Euro (€).

You can download my collected data in this spreadsheet or directly click on Get the data within each plot.

Q1: How much a PhD student is paid?

Q2: Which countries consider a PhD student stipendiary/civil servant?

In the countries where PhD students are considered public servants, a set of rules are also applicable for them as for the normal university staff, such as pension, social security and residence status (for no-EU students).

Q3: How much does a PhD student pay to enrol for a program?

Most European countries apply a model of free higher education. The current data are for full-time PhD students from EU/EEA/Switzerland. It should be noted that administrative fees and personal insurance also exist in most countries making the tuition fees not completely out of charge (but within reasonable rates).

Q4: What is the minimum wage of each country?

The minimum rate of pay or minimum wage is a measure to evaluate what amount of money is required to live with minimal conditions in a country. The rates are subject to modification every year based on many factors such as inflation rate and gross domestic product.

In the following plot, the monthly minimum wages (bi-annual data 2020) of our target countries are provided. These rates represent gross salary.

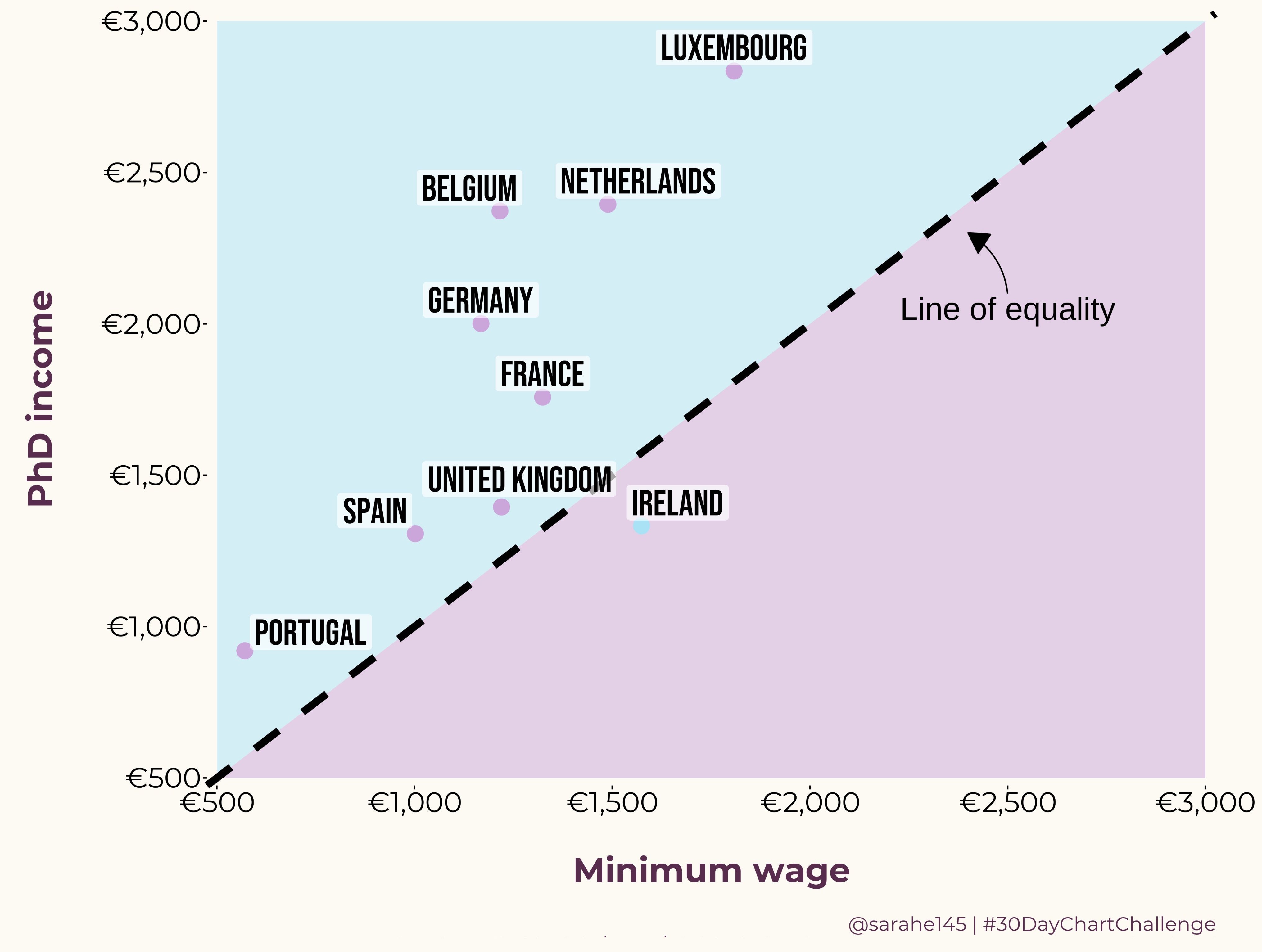

We can compare the minimum net wage rates with the minimum PhD income to find out how sufficiently a PhD student is paid as follows:

Based on this data, Sarah Ennis created the following more beautiful plot (Thanks Sarah!):

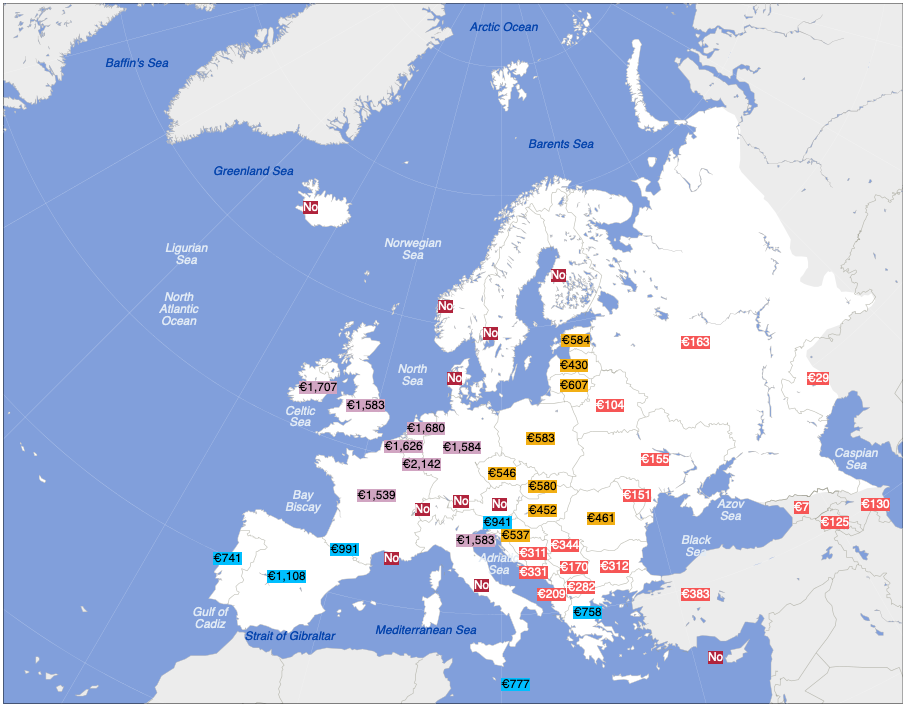

Q5: How much is the average rent for a 1-bedroom flat?

Paid teaching duties: a trivial but important source of extra income

In many countries, PhD students do a certain amount of paid teaching hours to earn some extra money. Deprived of such opportunities, PhD students in Ireland teach without being paid. This not only demoralizes students to get involved in teaching activities, but also makes them finish their PhD courses with a less interesting CV than other students in the mainland Europe.

Irish residence permit: a deal breaker?

One major difference in doing PhD in any other country in the EU in comparison to Ireland is the residence permit. The residence permit in Ireland is basically a certificate showing that you have a regular status in the country and you are not illegal. It doesn’t let you travel anywhere out of Ireland, even to Northern Ireland! While in the other EU countries, your residence permit is also a proof that makes it possible to travel freely in the other Schengen countries, from Cyprus to France, From Norway to Malta.

If you hold a passport that requires visa to travel to other European countries, you should think twice about the fact that Ireland is not in the Schengen area. That basically means that you won’t feel much European and will have to spend your time applying for visa every time you want to visit mainland Europe. On the other hand, with a residence permit from any other EU country, you have way more chances to appreciate the beauty of all countries in Europe!

For more information, check this out: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/moving_country/moving_to_ireland/rights_of_residence_in_ireland/registration_of_non_eea_nationals_in_ireland.html.

Conclusion

Here are the facts based on the collected data:

- Among all the Western European countries, Ireland

- is the only country where PhD students are paid less than the minimum wage.

- is the only country where PhD students are not paid for teaching activities.

- has the highest tuition fees.

- along with the UK, Spain, Belgium and Portugal, are the countries where PhD students are paid a stipend and have no public service status.

- along with the UK, have the highest rents.

I am not going to draw any conclusion from the data shown here. I believe that every one, depending on his/her life conditions, would evaluate the answers to the aforementioned questions differently. I am sure the reader knows that things are not always black and white and any comparison should be made in a fair way.

Last updated on 7 October 2021.